How one photojournalist is documenting sexual assault in the U.S. military

Mary Calvert is showcasing the true power of photojournalism, documenting injustices ranging from uranium contamination in the Navajo Nation to obstetric fistula — a debilitating medical condition which happens when women are injured during childbirth without timely access to medical care — in sub-Saharan Africa.

For the past decade, Calvert has focused her attention on documenting the pervasive and underreported sexual abuse of men and women in the United States military. Calvert has won the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award twice and is a three-time Pulitzer Prize finalist in the Feature Photography category.

Storybench spoke to Calvert about her experience covering sexual assault in the military and how she uses photojournalism as a tool to affect social change.

The following interview has been edited for clarity an length.

Quite a bit of your work is focused on uncovering underreported stories. How do you find stories like these to cover and how did you specifically come to cover sexual assault in the military?

My husband told me, “You ought to be looking into sexual assault in the military because it’s a terrible problem and nobody’s doing anything about it”… And I thought, surely that’s not happening here. Then I did the research. I started the project in 2013, and that year there were an estimated 26,000 sexual assaults in the military. And it just blew me away. After I couldn’t get any people from NGOs to even return my emails, let alone talk to me, I started going to hearings on Capitol Hill.

I went and photographed this hearing where sexual assault survivors were telling their stories to lawmakers. I went up to the side of the room to try to get an overall picture. And I stood there. I realized there were two still photographers there that day and I think there were four or five lawmakers. There’s four or five seats that were filled in that big room and I thought, “I can’t believe this. What the hell is going on?” That really gave me a lot of incentive to tell that story because it made me so angry.

I had nobody interested in it. I had not talked to any news outlet about it at all. I just knew that wild horses could not drag me from telling this story. My driving force was because it is so important. Photojournalism is about fidelity to your subject. The world is not your art gallery. You have a responsibility to tell stories with integrity and your subject’s dignity always intact. That’s what I try to do.

A lot of your storytelling in this social justice area seems very long-form. Can you talk a bit about your process and why this long-form work is used for this area?

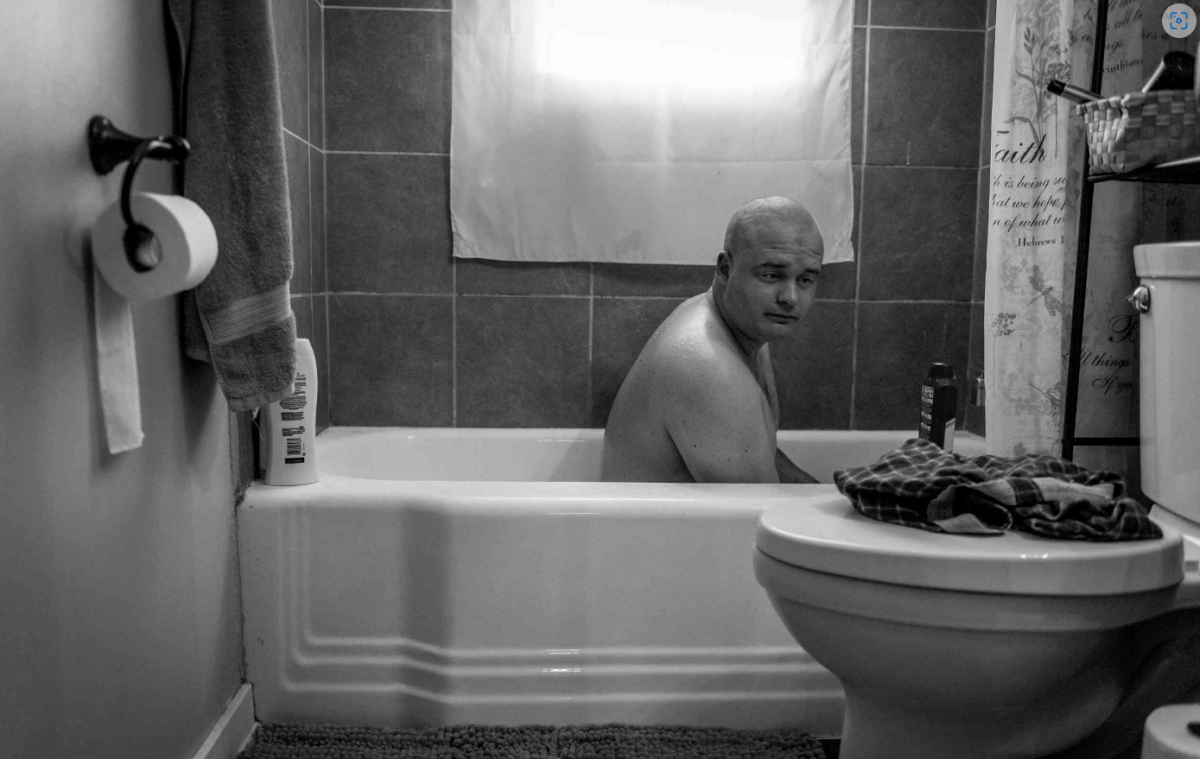

I want to show what their lives are really like. I don’t think you get that from just a portrait. It’s the pictures that happen in the middle of the night and different times of the day. I want to give myself time to allow life to unfold naturally, instead of forcing. Because if you’re forcing it by a portrait, I just don’t think you’re really telling their story. You’re not really showing me what is happening in their lives.

Why do you think photojournalism is uniquely suited to tell stories of sexual assault or other stories that are deeply personal and traumatic?

I’ve photographed, in my career, so many situations: floods, firestorms, earthquakes where people have lost everything. As long as their families were safe, the two things I watched people lament over and over and over were their pictures and their pets. And I thought, that’s really interesting. To coin a term from a good friend of mine, it’s evidence of our existence.

I think we have to look at the issues that are happening in the world. Instead of saying, “Well, that’s their problem. That’s not my problem, so I can’t invest any emotional energy in it.” We need to think of it instead as, “This is our problem.” Because we’re all humans on this blue ball in the middle of the sky, the middle of the galaxy, in the universe. I just really think it’s important to know what’s happening in the world and to somehow care. That’s the job of the photojournalist, is to make you care.

What do you hope these projects will accomplish?

I continue to address this issue because I think the story of oppression and subjugation and abuse of people affected by sexual assault needs to be pursued with ongoing tenacity to illuminate not only its existence, but to look at its cause and effect. The problem’s not going away. No, in fact, it’s only gotten worse.

In September 2022, the Department of Defense released its annual report on sexual assault prevention, and that details the highest reported estimate of rape and sexual assault in U.S. military history. And the report shows that the number of service members confronted with unwanted sexual contact increased from 20,000 in 2018 to 36,000 in 2022.

Was there anything in your life that prepared you to take on such emotionally demanding work? Is there any way to prepare to do work like this?

I think it was just time. There are things happening that are really important that people need to pay attention to. That’s how I keep pushing myself. They deserve a voice. I started doing this because I thought that there are a lot of people that are pushed around in this world and don’t have a voice, don’t have agency and I think people deserve a voice.

That’s one of the reasons I keep telling this story is partly because it’s so big, but also because every time somebody sees it somewhere, that means there are many people who can no longer say it doesn’t exist, or it didn’t happen or they didn’t know it was happening.

Do you have any advice for aspiring photojournalists or photographers who want to do similarly social-justice focused work?

The moments are the most important thing. People say, “Well, what’s a moment?” This is the most simple way I can explain it: It’s your little brother’s sixth birthday party. The family’s around the table. Somebody brings the cake in and your brother gasps. That’s a moment. You bring your hand across your face. A look, a gesture. Those are all little moments. And those are the things that will make anything you ever shoot come to life. Whether it’s your brother’s birthday party or my project on military sexual assault. In every picture in between, there’s always some little thing that’s like an emotional and visual anchor that draws people in.